Joshua Wise is the founder of Crossed Purposes. Crossed Purposes is a website which engages pop culture and theology through reviews, discussion and a weekly podcast. It looks at video games, books, movies, television, and music from a number of different theological disciplines including Systematic, Historical, Liturgical, and Biblical.

BioShock Infinite, Irrational Games’ second BioShock adventure,1 is a masterpiece of world-building and a penetrating insight into the extremes of American civil religion, the nationalization of religious traditions, and the vicious cycle of isolation, division, and insular identities.

Like the first BioShock, Infinite introduces the player to a world of incredible detail and atmosphere. Whereas the first game brought the player to the underwater city of Rapture, founded on Ayn Rand’s Objectivism, Infinite brings the player to Columbia, a city in the sky. The year is 1912, and Columbia is a city of religious piety, based on the transformation of religious conversion. The overtones of the Latter Day Saint movement are significant here. Though, instead of leading the people west to the new Promised Land in Utah, the Prophet, Zachary Hale Comstock, leads the people to a new Eden in the sky. This new holy land is powered by tricks that no other American religious movement has ever been privy to. Quantum physics and tears in the space/time continuum play a significant role in the life and identity of Columbia.

The world that game designer Ken Levine and his team have made is fascinating on a number of levels. Playing the game is incredibly enjoyable as well, combining Vigors, which are similar to Plasmids from the first two games in that they give you magic-like abilities to cast fire or change enemies into friends, with pistols, rifles and machine guns that all feel better than their previous BioShock counterparts. The The audio recordings, called Voxophones, found throughout the world, continue to fill in the story as well as give texture to the floating paradise of Columbia.

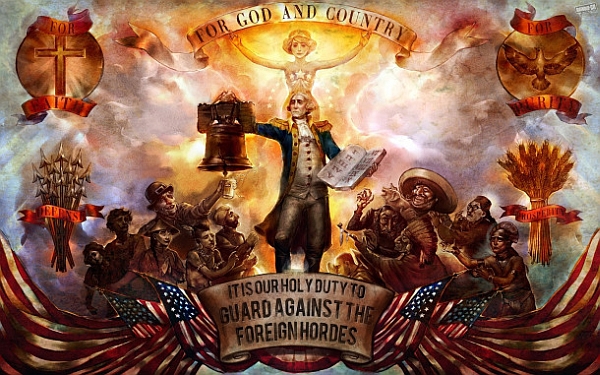

But one of the most interesting things for a theologian examining this game is how it portrays isolation and its resulting destructive power. The city of Columbia is a city of people who wished to escape the general society for something better. This is in keeping with many European and North American movements in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries. It is even reflected in both commune and cultist movements in contemporary times, and can still be seen in societies like the Quakers. The game reveals that this first step of isolation from the world below is followed by a second step. The city secedes from America after a conflict over its actions during the Boxer Rebellion in China. You learn fairly early on that racism is not only alive and well in Columbia, but is an institutionalized societal norm, very much as it continued to be in significant parts of the American south though the majority of the twentieth century. Not only people of African descent are marginalized, but the Irish are as well (an often forgotten piece of American racism). The employers are isolated from their workers, who are merely tools for their industrial machines. These divisions further and further isolate the privileged class of Columbia from the rest of the world and from their own society.2

A young woman named Elizabeth, referred to as “the Lamb,” is one of the main characters in the game, and is destined to succeed the Prophet when he dies. The Prophet has seen that she will rain “fire on the Sodom below.” But she is isolated in a tower, all by herself. She is the most cut off, the most treasured person in all of Columbia. Here the isolation is at its greatest. There is something of the ancient near-eastern idea of the concept of the holy and profane at work in this hierarchy or system of concentric areas of importance or purity. On the outermost ring is the world, the “Sodom below.” Next are the people, the workers and servants who are not worthy to be more than mere objects. Further up are the privileged, the white, moneyed, non-laboring pious decent people of Columbia. And there, in their middle, in the holy place where none may go, is Elizabeth, the Lamb who will lead them.

This is an image of religion at its monstrous height: dividing people, not uniting them. There is in it the very seed of hatred, the “us” and the “them”. The city, when Elizabeth is full grown, is to rain its fire down on the world below, the outermost ring of the world from which it sprang. But where would it go from there? Is not the next logical step to burn away the chaff of the underclass of Columbia? Then those who are no longer pure enough in the upper classes? The pattern is well known, written throughout the sad history of the centuries. It is the objectification of those who are not like us, the dehumanization of those who are “others” that leads to the very things that BioShock Infinite portrays. And, if this seems like a bit of a stretch, consider that every time a new Vigor is portrayed, the “enemies” are shown not to be people, but devils.

For what is the logical result if the center of the concentric circles is the holy one? The farther out you go, the less holy, the more demonic, the more in need of destruction. But this pattern plays itself out in another way in the world of BioShock Infinite. The outer ring not only holds the classes and races that the society finds undesirable, but also the past. Who people were before they came to Columbia is cast aside, and ultimately demonized. The people as Americans, even as Christians, redefine themselves in a new way by making devils out of their old self-identities. Just as the old selves are “killed” when a new life begins (drawing heavily from Christian religious imagery), the old self of America must be slain as well. This is reminiscent of many religious groups who, after dividing from their original body, anathematize that original body as heretical.

BioShock Infinite displays an amazing insight into the dangers of isolation, objectification, new identity, and the marriage of religious fervor, symbolism, language, and ritual with patriotism and tribe-like loyalties. What Ken Levine and his entire team did for Objectivism, they have now outdone with American Exceptionalism, and religious national loyalties. This is a very important game for the advancement of video games as a form of expression and as a center of discussion for important questions and topics.

1. BioShock 2, developed by 2K Marin, has some shockingly similar themes to this latest game. However, though the game was quite good, it has generally been overlooked since it does not come from the creators of the BioShock series.

2. The question as to where the disabled exist in the world is open. While people who are physically disabled are ridiculed and stuck into hulking robotic suits of armor so that they can “still be useful”, the mentally disabled are not significantly addressed. At least one peripheral conversation in the game, however, suggests that they are a shame to the families they are part of, and can conceivably be “taken care of” so that the shame will end.