An edited and updated version of this article is now available at Video Game Canon.

As video games begin to resemble film and television productions more and more with each passing generation, it’s interesting to observe that puzzle games remain a vibrant genre. Puzzle games burst onto the scene at the very beginning, back when gaming was nothing more than a handful of pixels projected onto an old television. While everyone in the “real world” was attempting to master a Rubik’s Cube in as few moves as possible, gamers were tackling the line destruction of Breakout and the line construction Tetris. However, without realizing it, the puzzle genre became just as story-driven as everything else the game industry produces today.

It’s hard to pinpoint exactly when puzzle games started being produced with characters and, occasionally, a plot. But one of the newer games that best personifies this trend is the mobile blockbuster Threes. The goal of Threes is simple: slide around a series of playing cards on a 4×4 grid so that matching numerals are placed next to each other. When slid together, these numerals merge to create an even bigger number. Repeat until the board is full and you have no more moves.

But Threes does a lot with its simple conceit through expert music selection and the “face” given to the game’s cards. Every card is white with a thin slice of yellow running along the bottom. Each slice has two dots for eyes and a small mouth that responds to events on the board. When two cards that match first join the board, they let out a shout and do a little dance. Each card has a unique name and voice, and some are even given other accessories (for example, Card #192 has fangs and is wearing headphones). And when those cards get close to each other, their expressions change to acknowledge their new friend. And thanks to the funky background music, I’ve heard Threes referred to as “the ultimate party simulator.” The player is actually meant to be the host, pushing party guests with similar interests towards one another. And when two cards occupy the same space, that is meant to show two people merging their separate discussions into a single conversation.

But Threes does a lot with its simple conceit through expert music selection and the “face” given to the game’s cards. Every card is white with a thin slice of yellow running along the bottom. Each slice has two dots for eyes and a small mouth that responds to events on the board. When two cards that match first join the board, they let out a shout and do a little dance. Each card has a unique name and voice, and some are even given other accessories (for example, Card #192 has fangs and is wearing headphones). And when those cards get close to each other, their expressions change to acknowledge their new friend. And thanks to the funky background music, I’ve heard Threes referred to as “the ultimate party simulator.” The player is actually meant to be the host, pushing party guests with similar interests towards one another. And when two cards occupy the same space, that is meant to show two people merging their separate discussions into a single conversation.

Players interact with numbered playing cards to play Threes, but the game’s use of numbers is actually completely superfluous. There’s no math involved in Threes’ card matching, and they could actually depict anything and the game would still play exactly the same. But by making them pseudo-people, the three creators of Threes deepen our connection to the game.

While Threes personifies its characters in subtle ways, other developers have chosen a much more overt strategy. Shigeru Miyamoto famously once said that he considers all of Nintendo’s characters a repertory company of actors. Mario is not a plumber who was sucked into the magical Mushroom Kingdom. Instead, he’s an actor playing a role. The theory explains how Mario can spend an entire game bashing Bowser for kidnapping the Princess and then turn around and spend a fun afternoon go-karting with the big lug. It also explains how he can don a doctor’s white coat and dispense vitamins in Dr. Mario.

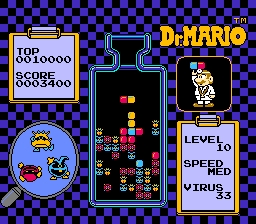

Dr. Mario’s puzzling premise is just as simple as Threes. A vertical board full of tri-colored “viruses” have to be removed by matching them with three “vitamins” of the same color. Again, the “viruses” could be anything (their faces are actually too small to make out on the board), and the “vitamins” are just a facade laid over a simple game of color matching. But thanks to the game’s vertical board, Nintendo is able to literally fill in the edges and give the world of Dr. Mario something extra. The “vitamins” themselves are doled out by a random sequence deep within the game’s programming, but because the right side of the screen shows them being dispensed by Dr. Mario, the player is able to picture the plumber as his or her helper. A magnifying glass on the left side of the screen shows a closeup of the three “viruses.” Each virus has a different personality and they will react in exaggerated ways as you clear the board of their offspring. With the viruses now large enough to see, you’re no longer doing color matching in a puzzle game, you’re defeating a foe.

Dr. Mario’s puzzling premise is just as simple as Threes. A vertical board full of tri-colored “viruses” have to be removed by matching them with three “vitamins” of the same color. Again, the “viruses” could be anything (their faces are actually too small to make out on the board), and the “vitamins” are just a facade laid over a simple game of color matching. But thanks to the game’s vertical board, Nintendo is able to literally fill in the edges and give the world of Dr. Mario something extra. The “vitamins” themselves are doled out by a random sequence deep within the game’s programming, but because the right side of the screen shows them being dispensed by Dr. Mario, the player is able to picture the plumber as his or her helper. A magnifying glass on the left side of the screen shows a closeup of the three “viruses.” Each virus has a different personality and they will react in exaggerated ways as you clear the board of their offspring. With the viruses now large enough to see, you’re no longer doing color matching in a puzzle game, you’re defeating a foe.

Almost all of Nintendo’s classic puzzle games used a variation of this branding trick over the years. Yoshi, Yoshi’s Cookie, and Kirby Avalanche all used Nintendo characters as a wrapper over a tile-matching game. Sega even took Kirby Avalanche (known as Puyo Puyo in Japan) and rewrapped it with Sonic the Hedgehog characters and called it Dr. Robotnik’s Mean Bean Machine. Taito also did it with Bust-A-Move, a cannon-firing color-matching puzzle game where the characters from Bubble Bobble were plugged in as the cannon operators. And let’s not forget Peggle.

PopCap’s Peggle is another puzzle game that’s simple on the inside (use a cannon to shoot a little ball at a board covered in pegs) with a lot of characterization on the outside. Each of the “Peggle Masters” has a name and a backstory, but all they do is serve as a cover for a pretty standard set of power-ups. In a world where Grand Theft Auto V and Call of Duty: Ghosts sell millions of copies a year, conventional wisdom would state that giving the Lisa Frank treatment to a puzzle game (after all, Peggle’s mascot is a magical unicorn) would be the kiss of death. Instead, Peggle (and its two sequels) have become huge hits.

And what about our three examples from the top? Surely the hard lines of a Rubik’s Cube, Breakout, and Tetris could not possibly have character hidden within them? Well…

The Rubik’s Cube became the star of a short-lived cartoon, Rubik: The Amazing Cube. In the show, a magic Rubik’s Cube helped three children overcome their problems, which included an evil magician. Breakout eventually spawned an entire genre of block-breaking games and one of the first, Arkanoid, posited that the bar along the bottom of the screen was actually a spaceship and the metal ball was used to defeat aliens. As for Tetris, the original game didn’t give the pieces a personality, but who among us didn’t view the game’s piece selection AI less as a random sequencer and more as a malevolent entity who flooded the board with S and Z pieces while withholding line pieces. It knew! I swear it knew! Oh, and aliens would eventually find their way into the franchise courtesy of 2001’s Tetris Worlds, which recast the “Tetrominos” as extraterrestrials that just wanted to go home.

While we may think of the puzzle game as a personality-less entity that helped us goof off in class or filled in as a time-waster between “real” games, the truth is the puzzle genre is filled with memorable characters. And the secret to creating a puzzle game that lasts is to give it a personality that players can relate to. Or alternately, you just need to stuff a few aliens in there.