“What kind of video games do you play?” It’s a broad question that I often find myself faced with, to which I’d respond “adventure games.” That answer is then followed with an exhausting amount of game name dropping, that, in most cases, have nothing to do with the type of games I’m talking about. “You mean, like Zelda?” Not quite.

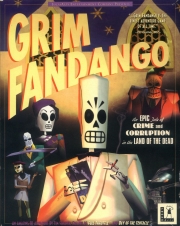

The easiest way to reiterate what I’m talking about is by calling them “point-and-click” adventure games, which is a genre and style of game most notable on the PC in the mid- to early 90s. It’s a genre that was also declared dead after the commercial failure of the critically acclaimed Grim Fandango; a genre that, over the past few years, has slowly but surely been coming back into the mainstream.

Broken Age’s Kickstarter success was the apex, arguably paving the way for other Tim Schafer games like Grim Fandango, Day of the Tentacle, and, most recently, Full Throttle to be remastered and re-released. This could have influenced Ron Gilbert — the godfather of the graphic adventure game — to also take to Kickstarter and successfully fund his nostalgic love child, Thimbleweed Park. Aside from well-known names in the genre returning to the medium that made their careers, several fresh-faced developers have been emerging over the years with new adventure games. The Dream Machine (Cockroach Inc.), The Journey Down (Skygoblin), and Dead Synchronicity: Tomorrow Comes Today (Fictiorama Studios) are a few that immediately come to mind.

Alongside the return of adventure games, an evolution of play-at-your-own-pace style gaming has emerged, with a deliberate focus on exploration, world building, and story – not just games that involve dying or killing. Most notably, games such as Dear Esther and Gone Home — two games derisively nicknamed “walking simulators” (a nickname that eventually stuck as their genre) — brought this style of game and storytelling to a contemporary mainstream audience. Their popularity has surely influenced audience’s perception of what games could be, and, by doing so, gave these “classic” adventure games an opportunity to resurface to a new audience that otherwise may have missed them the first time around.

Initially, the walking simulator started a rift in gamer’s views as to what should be defined as a video game, many making the argument that, without an obvious objective to defeat something or be defeated, it shouldn’t be considered a game. This idea of games not having a “game over” consequence is not a new concept, and was a common — and expected — trope of adventure games. This rift in what defines something as a game demonstrates the change of standard in gamers from generation to generation. From what I remember, this was not an argument that existed in the mid- to early 90s. So why now?

Walking simulators are, for the most part, adventure games but without the puzzles and heavy dialogue trees. Vanishing of Ethan Carter is a contemporary title that brilliantly balances the strengths of both genres. It allows the player the freedom to explore, to be given the story in a non-linear, unconventional sense, while introducing only a few puzzles along the way. Then there are contemporary games that directly challenge the adventure genre while still having its core mechanics, like Kentucky Route Zero. It features classic point-and-click controls, and, like walking simulators, leaves puzzles out, but is entirely dialogue driven.

Genres that challenge the perception of what games are expected to be today are coming back into style, and it’s owed to the return of adventure games. The adventure genre most certainly took a backseat in popularity, but still continued to influence new genres. In a weird twist of fate, adventure games were a catalyst in creating the walking simulator, and due to their success, may have brought the adventure genre back. Call it the circle of life, maybe. Or, I suppose, this is how trends go: the past influences the future, which in return references the past.

Adventure games never truly disappeared. Grim Fandango’s 100,000-500,000 sales were seen as abysmal in comparison to 1995’s Full Throttle that sold over a million copies. Grim’s commercial failure may have led to the cancellation of LucasArts adventures like Sam & Max Hit the Road and Full Throttle: Hell on Wheels, but other development studios have long kept the genre alive and well. One year after Grim, Norwegian game developer Funcom released The Longest Journey, followed by sequel Dreamfall released in 2006; French studio Microids released Syberia in 2002, with the third installment just released in April 2017; and Amantia Design released mega hits Machinarium and the Samorost series. The list goes on. Whether or not these were commercial “hits” is up for debate, but the genre has been far from dead – just not in the mainstream.

Adventure games never truly disappeared. Grim Fandango’s 100,000-500,000 sales were seen as abysmal in comparison to 1995’s Full Throttle that sold over a million copies. Grim’s commercial failure may have led to the cancellation of LucasArts adventures like Sam & Max Hit the Road and Full Throttle: Hell on Wheels, but other development studios have long kept the genre alive and well. One year after Grim, Norwegian game developer Funcom released The Longest Journey, followed by sequel Dreamfall released in 2006; French studio Microids released Syberia in 2002, with the third installment just released in April 2017; and Amantia Design released mega hits Machinarium and the Samorost series. The list goes on. Whether or not these were commercial “hits” is up for debate, but the genre has been far from dead – just not in the mainstream.

Genres come, but ultimately never go away. They evolve and take different forms, sometimes creating sub-genres. FPS’ have evolved and been reborn over and over again without ever losing the core value: shooting stuff from a first-person perspective. Control schemes have changed and so has technology. The industry has changed over the years, and the market has exploded and opened doors to new audiences and styles of game. Thankfully, slower paced, adventure-style games have come along with that. 2017 might be the year that I can finally mention “adventure games” and not have to explain exactly what I’m talking about.